Origins of Ko Huiarau

Rethinking the Treaty of Waitangi:

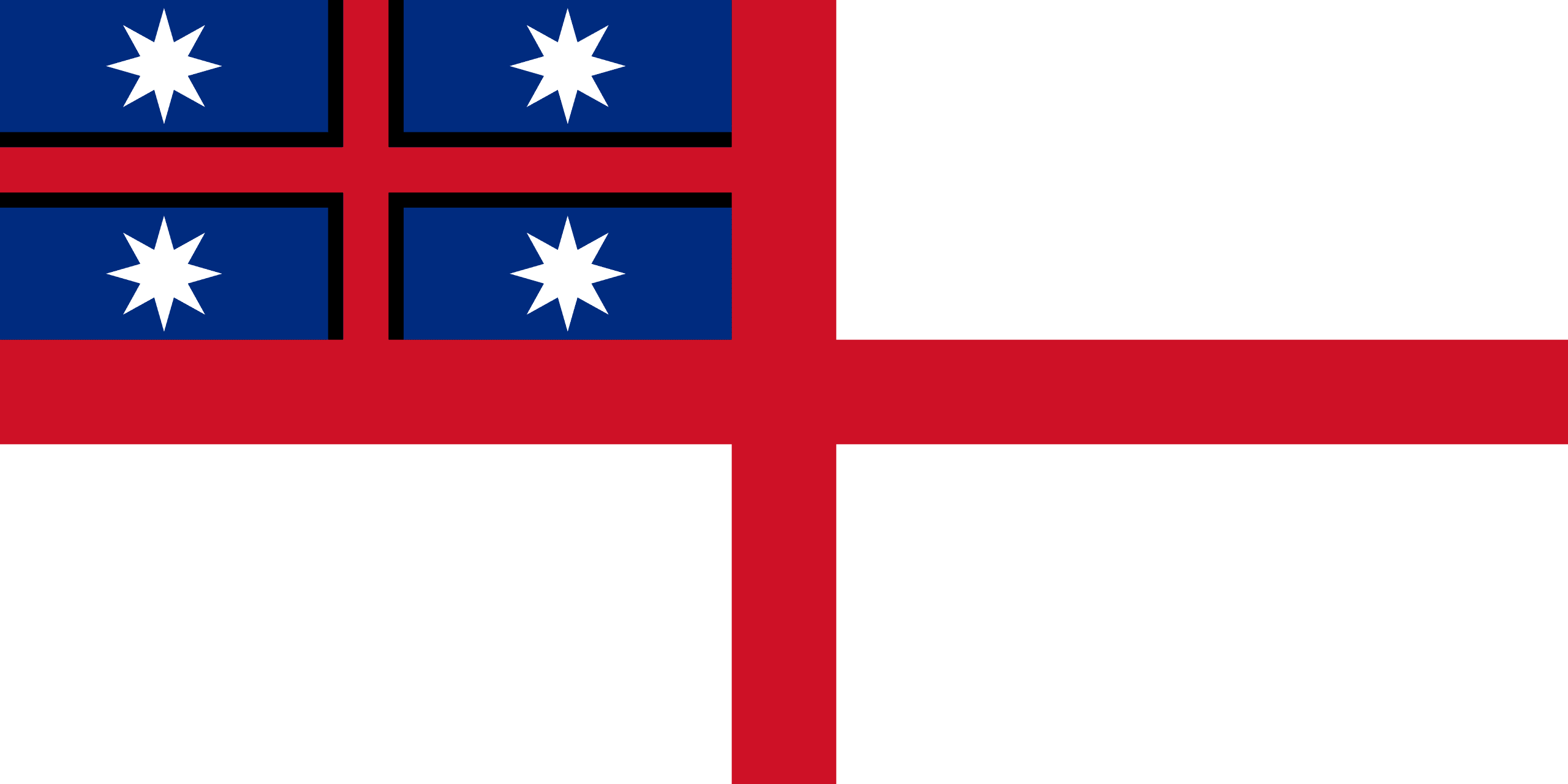

Ko Huiarau Sovereign Flag 1832 – 1861.

Granted by King William IV in 1832 in recognition that Aotearoa is its own Sovereign State.

Unity:

Vision Towards The Future

While the Maori name for the United Tribes is often spelt Ko Huiarau, it is correctly Kohuiaroa or Kohuiarau, both of which can be defined as a gathering at large and a gathering who are tied together. Just as the United Kingdom may be said to date from the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of England in 1603, so the United Tribes of New Zealand can be said to have begun in 1816.

Unite:

Plan to Further Unite All Tribes

It was at that time that Terehou of Ngai Tuhoe, having successfully led the united tribal armies of Tuhoe, Ngati Maramaru, Nga Herehere and Heretaunga against the incursions of the Warahoe hapu of Ngati Awa under Te Mautaranui, proposed a plan to further unite all of the tribes of New Zealand. The United Tribes were born.

Terehou’s plan operated on two levels, the first to unite the tribes by blood at the ariki level, the second, to unite the tribal armies in a common defence policy. Both of these were long-term projections. An immediate start was made on the defence policy, with each tribal area being organised into a series of defence positions tied into pa, defended gardens, storage areas and communications.

In 1836 three war canoes were constructed at Whakaki Lagoon near Wairoa and carved at Turanganui. These were to patrol the coasts against the main threat of that time, the northern musket raiders. One of these canoes is Toki a Tapiri, which became a koha to seal a peace contract with Ngapuhi and now rests in Auckland Museum.

Taiopuru Right

to Twenty-One Guards

Te Rangi Topeora of Ngati Toa and Ngati Raukawa was the second commander of the United Tribes following Terehou. She relinquished the position to her uncle Te Rauparaha. After his death in 1849 Te Rangi Topeora served again until her death in 1873, being succeeded by her daughter Topeora, also known as Tiopira of Ngati Kahungungu, Ngati Marumaru, Ngati Raukawa and Tuhourangi who disbanded the army. Today twenty-one guards are retained as a bodyguard for the Taiopuru.

Whakapapa

of the Taiopuru Lines

The plan to unite the bloodlines has perforce taken a long time.

- The first ariki Taiopuru of the United Tribes was Waikato Tairea of Nga Herehere, Ngati Maniapoto, Ngati Kahungungu, Ngai Tuhoe, Tuwharetoa, Taranaki, Nga Rauru, and Ngati Ruanui.

- The second Taupiri Whareherehere also of the above and Ngati Raukawa, Ngati Maru.

- The third, Noa Herehere Taronga Te Nuku, was also of Ngati Whatua and Ngai Tahu.

- The fourth, Taupiri Taronga Whareherehere, brought in the Nga Titoki and Ngati Porou.

- The fifth was Te Maremare Watene Haronga of Ngati Hineata of Ngati Porou, Nga Urewera and Ngati Whatua.

- The sixth was Noa Whareherehere also of Ngati Awa, Ngaiterangi, Mataatua.

- The seventh was ariki Taiopuru is Taiuru Tainui Waikato Wharehere of Ngati Hau, Ngati Rangi, Parawhau, Nga Titoki, Ngati Whatua, Ngai Tai, Te Aki Tai, Ngati Paoa, Ngati Hine, Ngati Mahuta, Ngati Raukawa, Ngati Maniapoto, Te Ati Awa, Ngati Rahiri, Taranaki, Nga Rauru, Ngati Ruanui, Ngati Maru, Ngati Pahau, Tuwharetoa, Ngati Awa, Nga Pourangahua, Nga Herehere, The Whatuiapiti, Takitimu, Ngati Porou, Nga Urewera, Te ATi Hau a Paparangi, Muaupoko, Ngai Tahu and Ngati Mamoe.

- The eighth and present ariki is Taiopuru Te Rauna III.